In this article we look at the symptoms of overtraining and talk to an elite cyclist and former Team GB canoeist about their experiences.

Intense, regular working out, running, cycling, CrossFit [insert your favourite sport or gym workout here] can be motivating & addictive along with a huge grin factor. Its fabulous to spend time doing something you love that is also making you healthier & stronger. However, endurance sports, explosive sports and gym-based workouts can lead to overtraining, or its less dangerous cousin – ‘overreaching’. This can seriously impact your training plans if aiming for an ‘A’ race or big goal.

Here’s how to recognise the signs and, if your training has taken you over the precipice:

The symptoms of Overtraining syndrome (OTS) include feeling rundown, an emptiness in the key muscle groups and not being able to complete your workouts. For example, a keen runner might feel heavy legged and may even be catching constant colds & suffering cold sores. Sometimes the fatigue is so great that mentally & motivationally, there is no willingness to train hard and for PTs your client may even dread that next session on the plan.

Use your Heart Rate… Regular measurement of resting heart rate (RHR) provides an indicator of overdoing it. Measure your RHR every morning for 2 weeks before you roll out of bed, count your pulse for 20 secs, multiply by 3 and record on a device beside your bed. An increase of more then 5bpm can be a sign of overtraining. Biochemically, an inability to take the heart rate into the higher HR zones during intense interval sessions is a key indicator that rest and recovery are needed and needed pronto!

What’s the difference between over-reaching and full-blown over-training? Talking to different fitness people and athletes, the differentiating factor seems to be the depth & scale of the tiredness. Full over-training takes longer to recover from, whilst recovery from over-reaching may take just a week. Initially thought the symptoms of deep fatigue, heavy legs and lethargy will be the same. Overtraining often occurs when athletes try to continue training & “push through” the fatigue.

You’ve overtrained, what do you do?

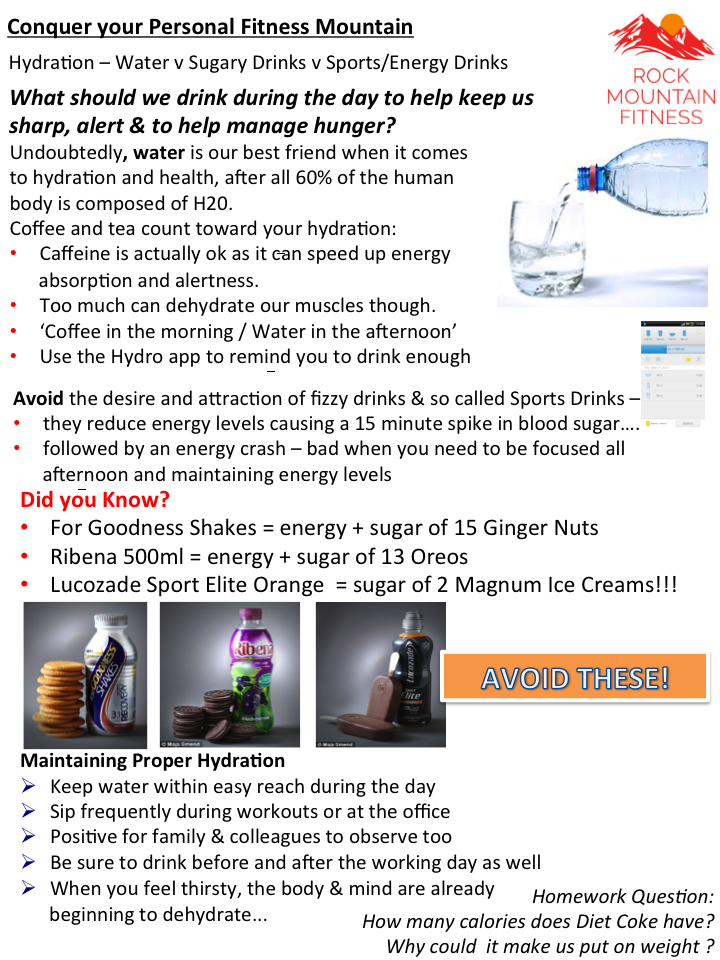

The first thing to do is plan your recovery – try halving your regime for 4 weeks to see if your mojo returns. That’s a shocker for the gym addict or runner who likes “to get the miles in”. Just imagine not being able to do your regular classes, the worry of weight gain and shape-loss, the void created by a lack of training…. The good news is that with quality rest, decent deep REM sleep & good hydration the body & mind can recover quickly.

What about the lost sessions? An approach I recommended to one of our aspiring Marathon clients, Sean Orford, was to focus on improving mobility and flexibility with Yoga & the foam roller. Sean did several days of Yoga and meditating back to  back. When he began to feel fresher, he returned to training at a lower intensity & distance. Staying in the lower heart rate zones also let the big heart muscle recover too.

back. When he began to feel fresher, he returned to training at a lower intensity & distance. Staying in the lower heart rate zones also let the big heart muscle recover too.

Overtraining doesn’t discriminate between amateurs and pros

The likes of our Team GB heroes Farah, Brownlees’ et al will suffer from over-reaching only occasionally thanks in part to being professionals and being paid to rest & adapt. Top amateur cycle racer David Zelaskowski holds a full-time job while also coaching aspiring cyclists. He gave up teaching Insanity fitness classes because he could not recover fast enough for his next hill repeats session or road race. As David puts it: “you can’t out-rest over-training and no matter how many ice baths you have you still don’t recover.”

He emphasises the need to have proper muscle recovery after hard workouts and also to have proper mental recovery too. In years gone by David had over-reached by working long hours, training hard and then racing. In races he noticed “a pattern of bad decision-making that meant I missed key breaks and sprints which was due to mental fatigue alongside physical training overload.”

Former Team GB canoeist Colin Cartwright now operating Cartwright Fitness supplies recalls “we used to train in the Eastern Bloc style… heavy volume training, sometimes 3 sessions per day – canoeing, strength & conditioning and do this on back-to-back days. I was regularly super-tired, going onto the water feeling lethargic and trying to train through it but not hitting the numbers I needed to.“ Cartwright learnt that 16k hard training on the river plus heavy resistance training in the evening doesn’t equal great results.

He says: “Nowadays I’d rather peak train for 12 weeks within the year than train full-on for 52 weeks. Listen to the body, its hard to back-off but you will get stronger in recovery. My times now, on lower volume but better quality training are as good as they were 10 years ago…. Makes me think what I might have been able to do with better recovery patterns built into the plan”

Even most pro-athletes don’t complete the year without injury & fatigue and they eat properly and they train correctly, they have the expertise of coaches, physiotherapists, nutritionists and sport scientists to support them. (And they don’t have to contend with late nights, demanding bosses, family commitments, full-time jobs and other commitments, like the rest of us.) The only stress on their system is exercise, whilst for the average recreational exerciser stress bombards us from all angles.

In our next article we’ll factor in the effect of poor nutrition, particularly inadequate calorie intake, and insufficient carbohydrate and water consumption and the effect that has alongside overtraining.

Lift Heavy or Stay Home – Yours in Running

Conrad Rafique is a Fitness & Motivation Coach and runs Rock Mountain Fitness. He graduated as a Master Trainer from The European Institute of Fitness and has competed in a range of Trail Marathons, road marathons, Halfs and 10ks. He has recently returned to the track with new spikes.